Janice Light ( Penn State University) describe strategies for maximizing the literacy skills of individuals who require AAC. This webcast was produced as part of the work of the AAC-RERC under grant #H133E080011 from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR)in the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services (OSERS)

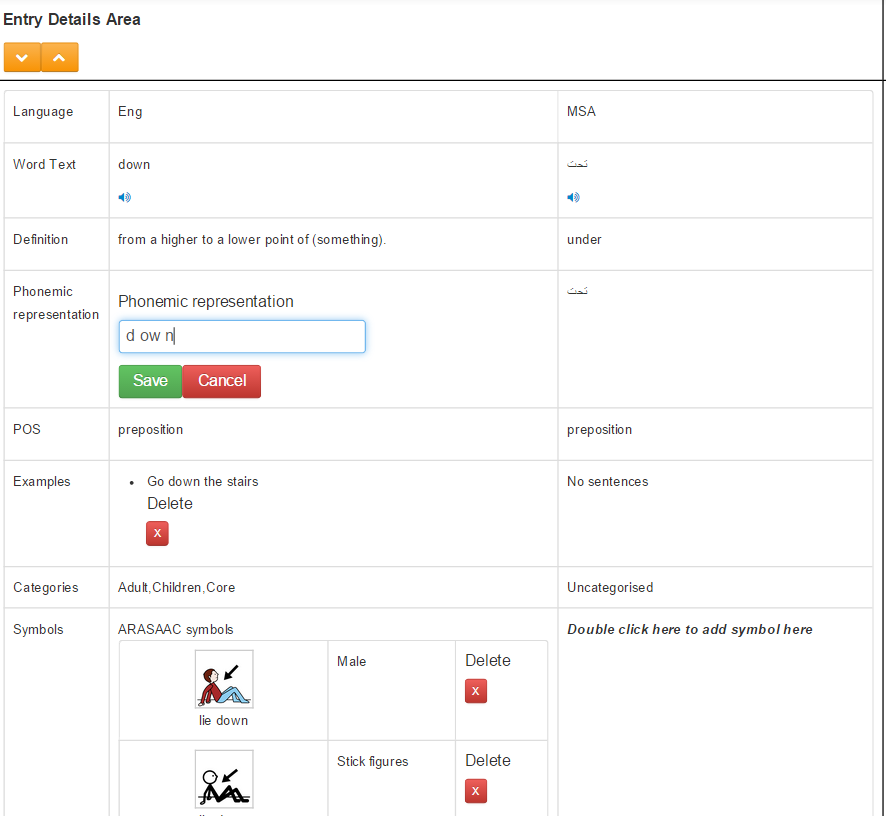

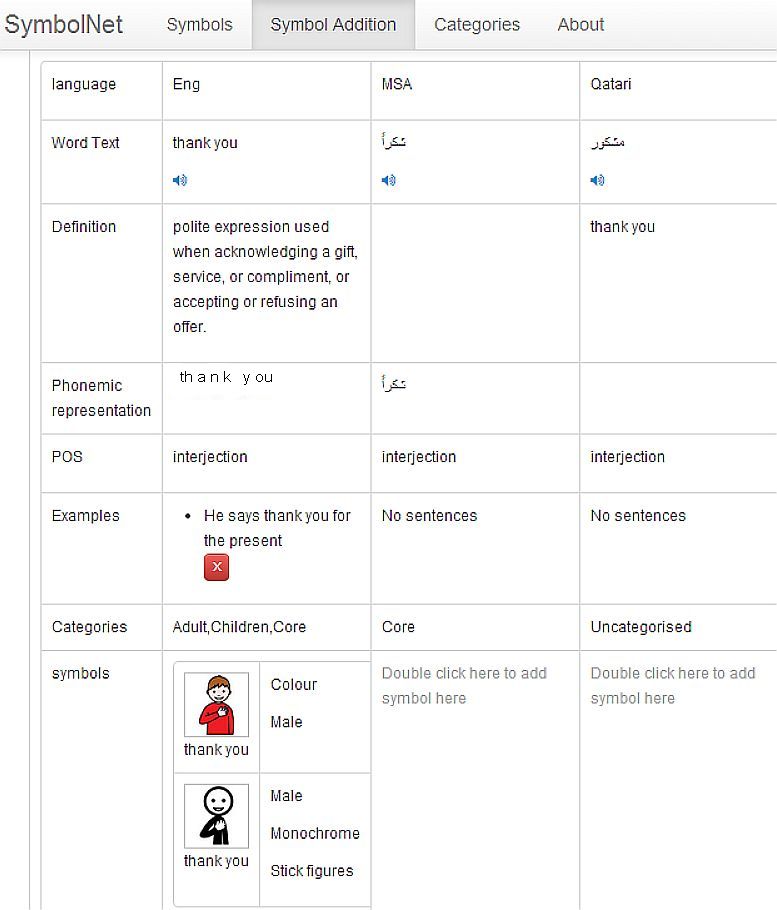

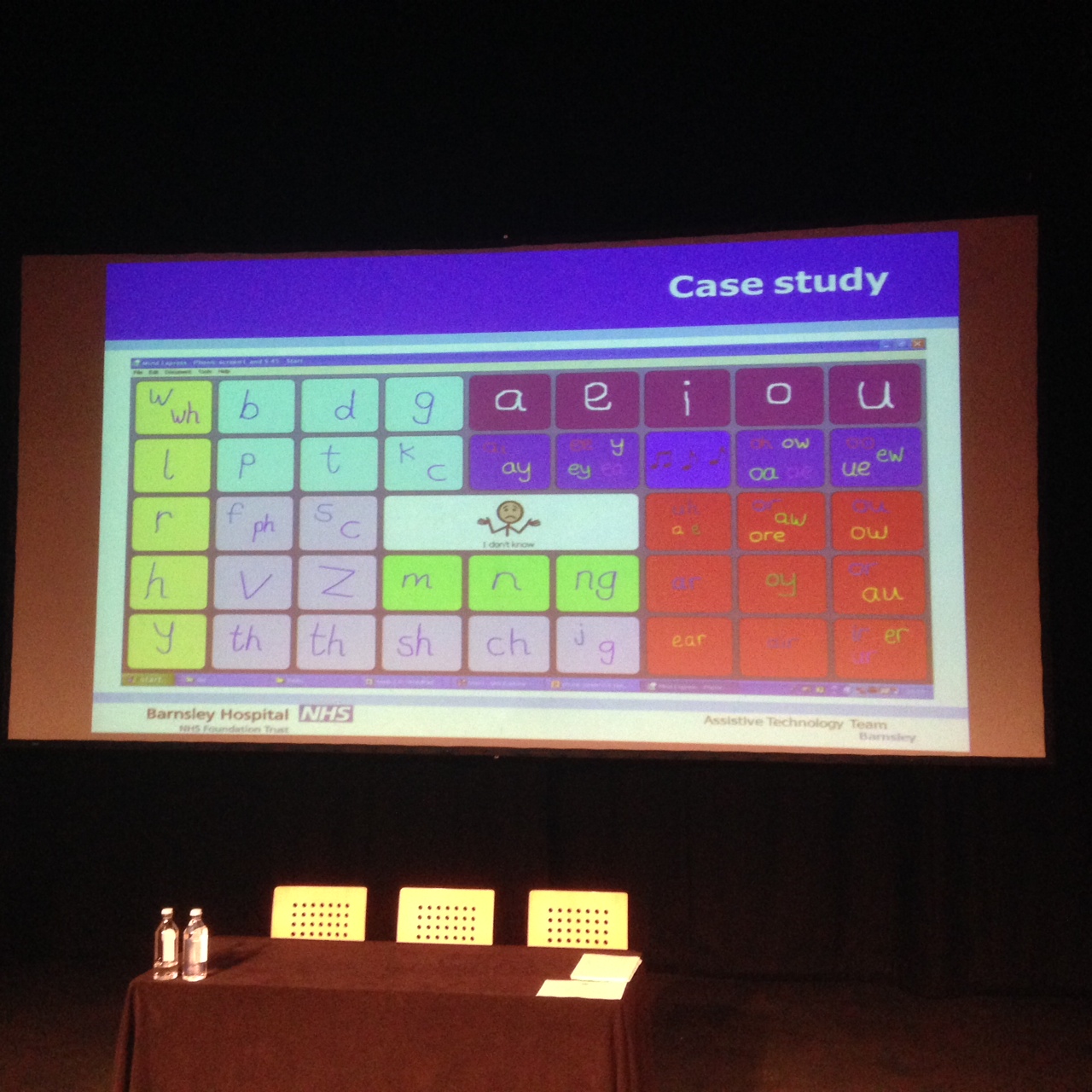

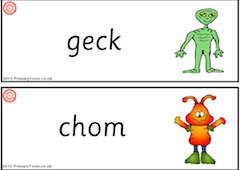

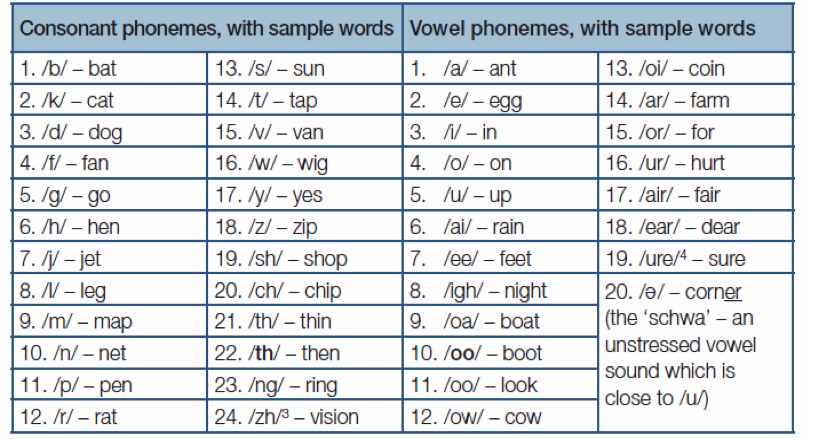

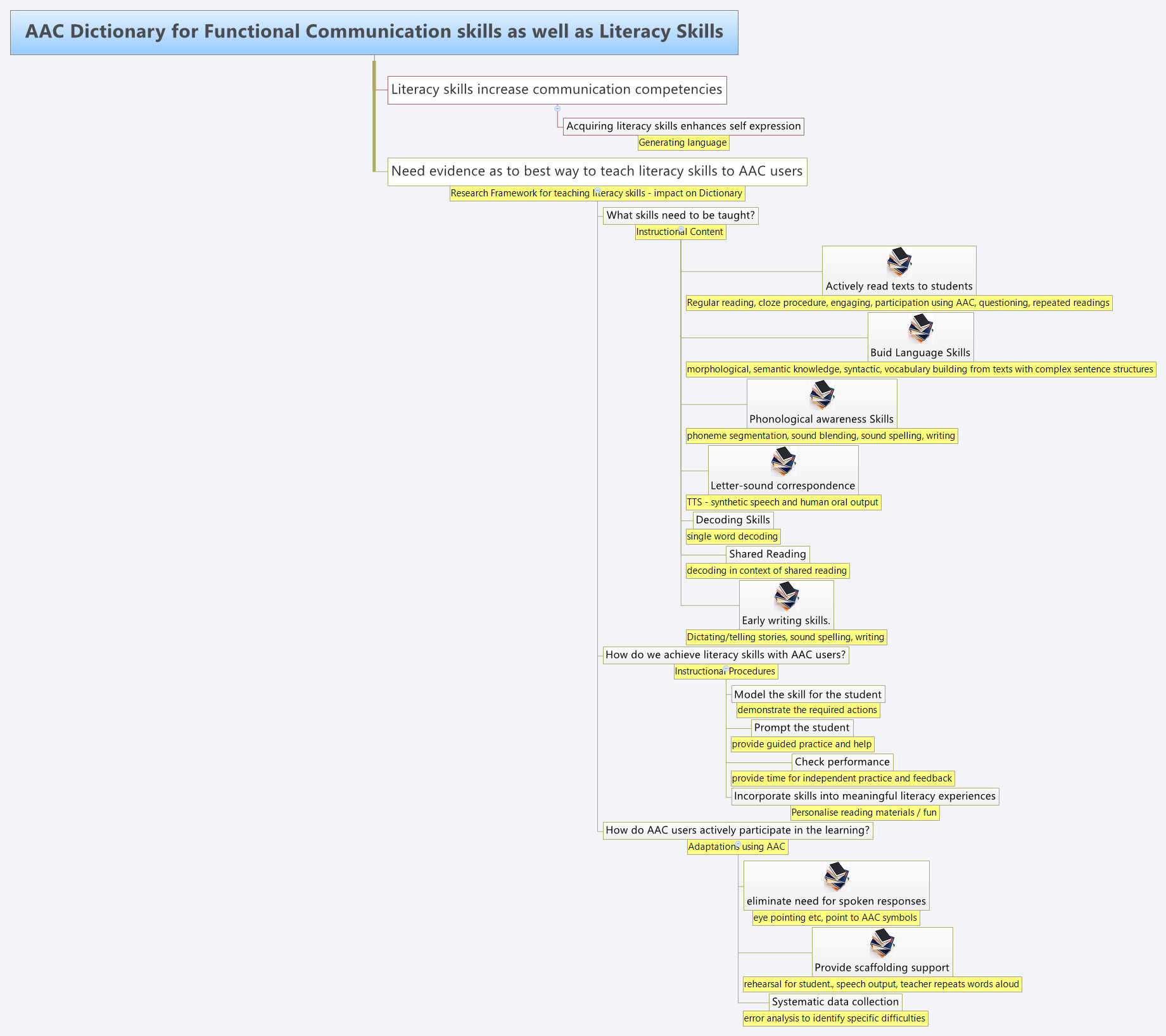

In recent years there has been increased interest in teaching literacy skills to those who use AAC and one particular research project on Literacy Instruction led by Janice Light and David McNaughton at Penn State University in the USA has resulted in a very useful resource. Not everyone agrees about how this task should be achieved and there remains the dilemma around the amount and type of symbols that should be used to support the learning of words with letter combinations especially where phonics is involved and bilingualism.

Here Jane Farrall highlights other issues in her article “Symbol Supported Text: Does it really help?” and cites Erickson, Hatch & Clendon (2010) who also say:

For multiple reasons, pairing picture symbols with words may limit access to learning to read. Pictures actually may increase confusion, especially when they represent abstract concepts, have multiple meanings, or serve more than one grammatical function (Hatch, 2009). This is particularly true when words do not have obvious picture referents, as is the case with verbs such as do and is. Because they do not have picture referents, they must be represented by abstract, arbitrary symbols […]. While the orthographic (print) representation of these words is also abstract, printed words appear much more frequently and are understood more broadly than are abstract picture symbols. As a result, students learning to read the words rather than recognize the abstract picture symbols have more opportunities to encounter the words and interact with others who understand them.

We have already discussed the issues about learning the sounds that make up the various parts of words along in a previous blog and the Tawasol website offers text to speech to support the syllables and diacritics that aid the learning of phonemes. But there is a problem when learning individual letters as they change their sound when said in isolation. The text to speech does not always make a good job of the sounds required so it may be that we will need to use recordings for this element.

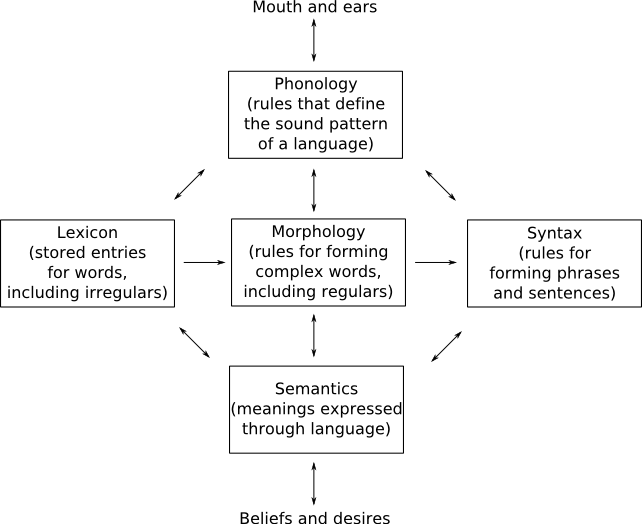

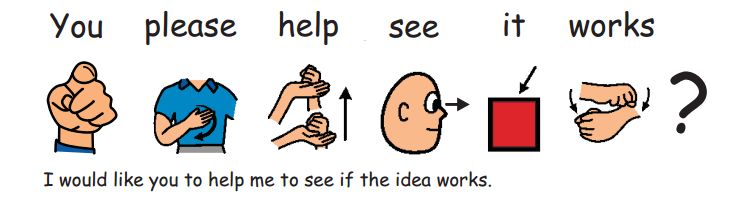

in the meantime there is also the issue of how much symbol support is provided when learning groups of words or small linking words such as conjunctions, prepositions etc. Some speakers such as Marion Stanton illustrate the problem very vividly in a talk about “Supporting students who use AAC to access the curriculum”. when working with an older student and others such as Professor Janice Murray have also shown in their slides about Language, Literacy and AAC the problems when words may not have any representative symbols or have very different meanings in certain situations and how a simple word symbol matching system will not work.

Sample of text and symbols taken from the Dundee StandUp project consent form

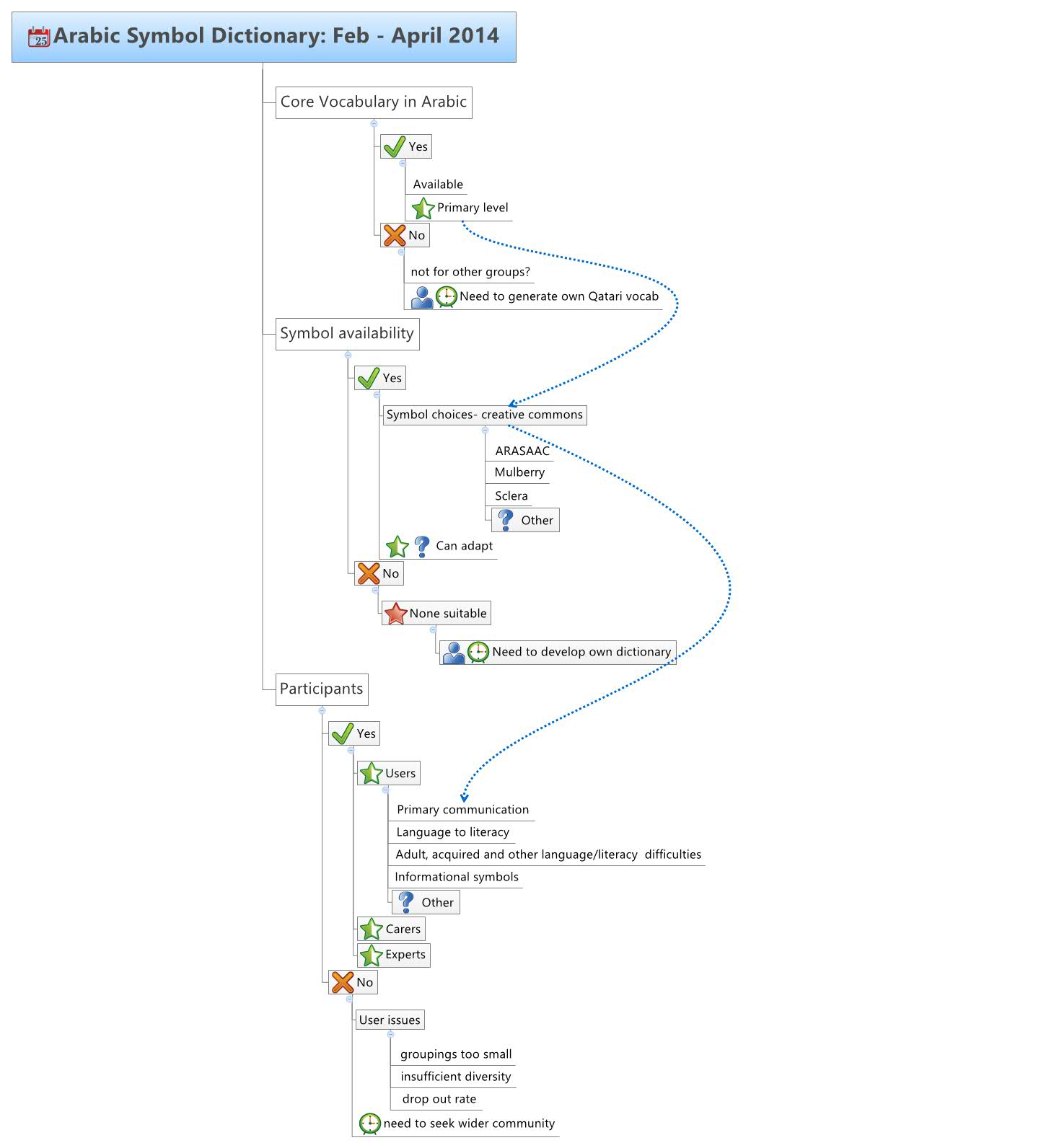

The symbol dictionary team have been debating how to make supportive information and booklets available using the Tawasol symbols knowing that this is an important subject and one needs to start when on the journey to reading and writing as soon as possible as suggested by Carole Zangari in her ‘Lessons for Beginning AAC users‘ .

The issues that have been discussed have begun with such simple concerns as

- Should text be above or below the symbols? See Cricksoft’s practical point and looking at all the handouts it seems to depend on personal choice?

- Should the accurately written sentence appear below or above the symbols or each symbol match a word?

- Should some words remain as words or always be translated into representative symbols even if the result is not always an easy one to interpret?

With grateful thanks to ARASAAC for all their support in this project

Some of the abstract linking words or conjunctions and prepositions simply do not work in a bilingual dictionary situation. This may be due to the position and direction of an arrow due to the right to left and left to right directions of the text or it may be the fact that a simple mathematical symbol may be easier to understand when compared to an unknown image. There is also the thought that it might be easier to learn a word such as ‘of’ instead of showing it as and ‘from’ and research has shown that there may be times when not working with the actual words slows literacy skill progress.

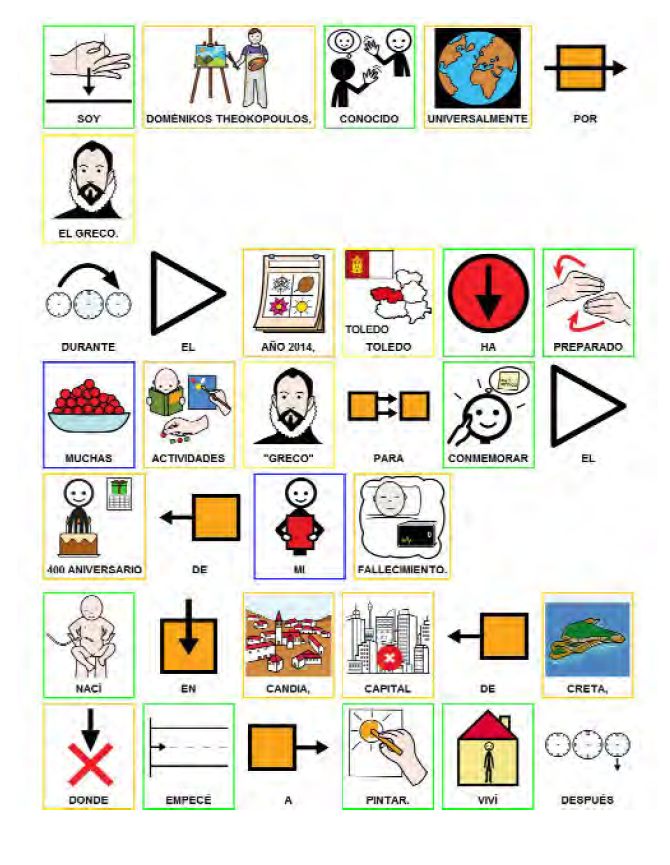

On the other hand even though you may not speak Spanish this page illustrates how a booklet with supporting symbols can explain a piece of history where learning to read is not the main aim. Here the goal is to communicate a story for knowledge building and enabling all those involved in the visit to the museum to have an inclusive experience. This image has been taken from a booklet about El Greco developed by Dirección General de Organización, Calidad Educativa y Formación Profesional de la Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deportes de Castilla-La Mancha.with pictograms from Sergio Palao. Procedencia ARASAAC (http://arasaac.org). Licencia Creative Commons (BY-NC-SA).

It is felt that when developing AAC materials they will nearly always need to bespoke, but when they are being offered for general use there needs to be a clear understanding as to their intended use. As can be seen in this short article the needs of the AAC user may vary enormously depending on their abilities, skills and situation as well as the type of teaching task and resources available. communication and knowledge building may well be aided by the combination of symbols and text. However, literacy skill building may require other types of strategies and different learning materials.

References

Erickson, K.A., Hatch, P. & Clendon, S. (2010). Literacy, Assistive Technology, and Students with Significant Disabilities. Focus on Exceptional Children, 42(5), 1 – 16. (Accessed 11 Dec 2015) https://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-240102195.html