Over the past 2 months I have visited approximately 10 sites across Doha including special needs schools and centres, outpatient speech pathology services and clinics, and child development centres. I have met many wonderful teachers, therapists, support staff, parents, and AAC/symbol users. Throughout my visits, there have been some challenges, but mostly optimism and willingness from support staff to help our team develop the Arabic symbol dictionary.

Through my experiences I have had unprecedented insights into the challenges support staff, symbol users and parents face here in Qatar. The following are some of the things I have gathered from my interviews with support staff of symbol users.

The need for an Arabic and English symbol dictionary

Although this project aims to develop an Arabic symbol dictionary, through discussions with support staff of symbol users it has become apparent that the integration of English into the symbol dictionary is vital. This is due to a few reasons;

- With the exception of 2-3 centres in Doha, the majority of therapy and education in Qatar occurs in English. As the majority of support staff come from abroad to work in Qatar, English is very widely used across Qatar.

- People in Qatar are not exclusively Qatari with expatriates comprising 86% of Qatar’s population (Qatar Supreme Council of Health, 2012). Qatar showcases a myriad of cultures most of which, speak English. Therefore, an Arabic only symbol dictionary would only serve the needs of a fraction of symbol users in Qatar.

- It is common in the Qatari lifestyle to have a maid and a driver. These workers usually come from the Philippines, Nepal or India and usually speak to the family they are working for in English. The nanny usually spends a large amount of time with the child/children and communicates to them most commonly in English. Therefore even for Qatari children it is important that English symbol options are available.

Cultural appropriateness of the symbols

All the therapists I met with agreed that there is a need to make the current symbols used in Qatar culturally appropriate. This is also reinforced by the findings of Hock & Lafi in 2011 who state that ‘Icons or symbols used for AAC systems such as Blissymbols2 and Picture Communication Symbols3 (PCS) are designed to suit western culture and to be written from left-to-write and are therefore not suitable for Arab users’. Here are some examples I found on my visits which show how symbols used in Qatar lack cultural appropriateness.

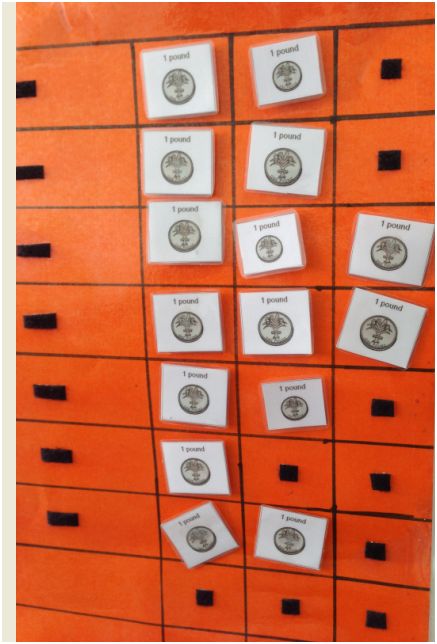

At one centre, a class of approximately 20 students with a range of conditions including Autism, Down’s syndrome and cognitive impairments all love one specific activity organised by their teacher, a shopping trip. The support staff use the symbol of a coin as a reinforcer throughout the week for good behaviour (image below). At the end of the week the students go shopping at the store close to the centre and depending on how many coins they have accumulated determines how much they can buy from the store. There is only one problem. The symbol for money is ‘one pound’ where as here in Qatar we use Qatari Riyals. For children who already have cognitive challenges and communication difficulties, this can be a very confusing concept to grasp. As we know, children with Autism for example are known to be literal or ‘‘concrete’’ in their thinking (Mesibov, Adams, & Klinger, 1997 in Trembath, Balandin & Rossi, 2005). Due to the difference in perception, they require consistent teaching and consistent feedback from adults and other children to learn effectively.

Upon interviewing a clinical psychologist at a special needs school, she recounted her experiences working with a young Qatari boy. In an activity working on a social story of a boy who went to the park with his family she realised that her student was very confused. She reported that the story and symbols didn’t have a nanny in it and the nanny is the one who usually took him to the park. She also mentioned that through her experience, the family portrait type symbol for family could not reach out to all Qatari children because the family dynamics of the family here are quite different to that of a western family.

Most importantly, the family members in the symbol didn’t look like the normal Qatari family. Take for example the symbol for the mother who is portrayed as having blonde hair and wearing a t-shirt. Conversely, the Qatari mother would most likely be wearing an Abaya (black long dress-covering the whole body) with a hijab (head-scarf). As the research suggests; differences in the perception of symbols can result in “teaching unintended or incorrect meanings for symbols, responding differently to the use of these symbols…and this may have consequences for the child learning AAC, as competent use of AAC systems must be taught” (Trembath, Balandin & Rossi, 2005). This poses many challenges for symbol users in Qatar and support staff in trying to teach them symbols which lack cultural suitability.

Furthermore, numerous teachers communicated that for this dictionary to be effective and to be used widely, the symbols must accommodate for the diversity of the Qatari population. Alongside a symbol of a man wearing traditional Qatari clothes should be an American looking man as well as a Phillipino looking man. This should be the same as the symbol for rice, as there should be a symbol for Machboos rice for Qataris, Fried Rice for Philipinos and Biryani rice for Sub-continental people. In their experience it has caused many communication breakdowns as a Qatari child cannot relate to a fried rice symbol nor can a Philipino child relate to a Machboos symbol nor can any of them relate to a generic symbol for rice. This echoes the findings of Huer 2000 who states that those with different language and life experiences do not perceive graphic symbols in the same manner.

At another centre I visited they used both English and Arabic symbols depending on the needs of the child. They kindly showed me some of the Arabic symbol strips used (attached). The speech therapist had obtained the symbol strips using BoardMaker’s latest Arabic version of the PCS symbols. It was alarming to see how many inaccuracies were portrayed in the symbol strip without the support staff knowing. This is because they are not from Arabic speaking backgrounds and had no choice but to rely on the Arabic version of PCS. Some of the errors included;

- Symbol strip ordered from left to right (English order) for an Arabic sentence

- The words used were inaccurate and did not make sense. If the content of the strip was translated word by word it would be correct but in the context of the task, it made no sense e.g. ‘reach your arms to’ was translated in Arabic as ‘make your 2 hands arrive to’

- Interchangeable use of tense within the same strip

- Incorrect grammar – the verb ‘dry’ translated into Arabic as adjective for ‘dry’

It is for these reasons that our project has chosen to use a participatory research methodology as symbols should be selected and modified in consultation with consumers, families, and practitioners especially in situations where practitioners provide support to individuals with cultural/ethnic backgrounds different than their own (Huer, 2000).

Parent awareness

One teacher highlighted the need for our team to educate parents on how to use symbols at home. She recounted a few incidents with Arab and Qatari parents speaking to their child attending the centre in broken English. They believed it was the best for their child given their teachers, therapists, and nannies speak in English. The teacher was concerned that this further isolates the child from the rest of the family as the rest of the family mostly speaks Arabic. The child can’t interact with cousins and family friends and is seen as different because he/she is the only child that the family speaks to in English. This may make the child feel that he/she doesn’t ‘belong’ in the home environment.

Overall, my interviews were very insightful and many issues arose regarding issues with current symbols used for children in Qatar. It gave our team many interesting things to ponder about and many challenges to overcome. It is through these interviews that it was reinforced to me and our team the great need for the Arabic symbol dictionary here in Qatar and across the Arab world. Our team are very hopeful that through this project, symbol users in Qatar can have the opportunity and the liberty to communicate the way they need to in their given environment.

References

Hock, B. S. & Lafi , S., M. (2011). Assistive Communication Technologies for Augmentative Communication in Arab Countries: Research Issues. UNITAR e-Journal, 7(1), 57-66.

Huer, M. B. (2000). Examining perceptions of graphic symbols across cultures: Preliminary study of the impact of Culture/Ethnicity. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 16(3), 180-185.

Trembath, D., Balandin, S., & Rossi, C. (2005) Cross-cultural practice and autism. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 30(4), 240-242.

Supreme Council of Health, Qatar(2012). SCH Annual report 2012. Doha, Qatar. Retrieved from http://www.nhsq.info/app/media/540.