I have begun to look at the impact that wishing to extend the symbol dictionary to one that will also enhance literacy skills may have on the project design. The first presentation I came across has provided some guidelines for those supporting English AAC users and is backed by research funded in USA – AAC-RERC is a Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center that functions as a collaborative research group dedicated to the development of effective AAC technology. I wanted to see where text to speech (speech synthesis) could help and see how the need to include not just the alphabet with sound support, but also letter combinations, blending and segmentation that help with reading and spelling might also need to be in place, bearing in mind this is not necessarily the case in Arabic. That will be the next stage of the research.

There is a presentation provided by Professor Janice Light (Penn State University) describing the components of effective literacy interventions for individuals who require AAC called “Maximizing the Literacy Skills of Individuals who Require AAC”

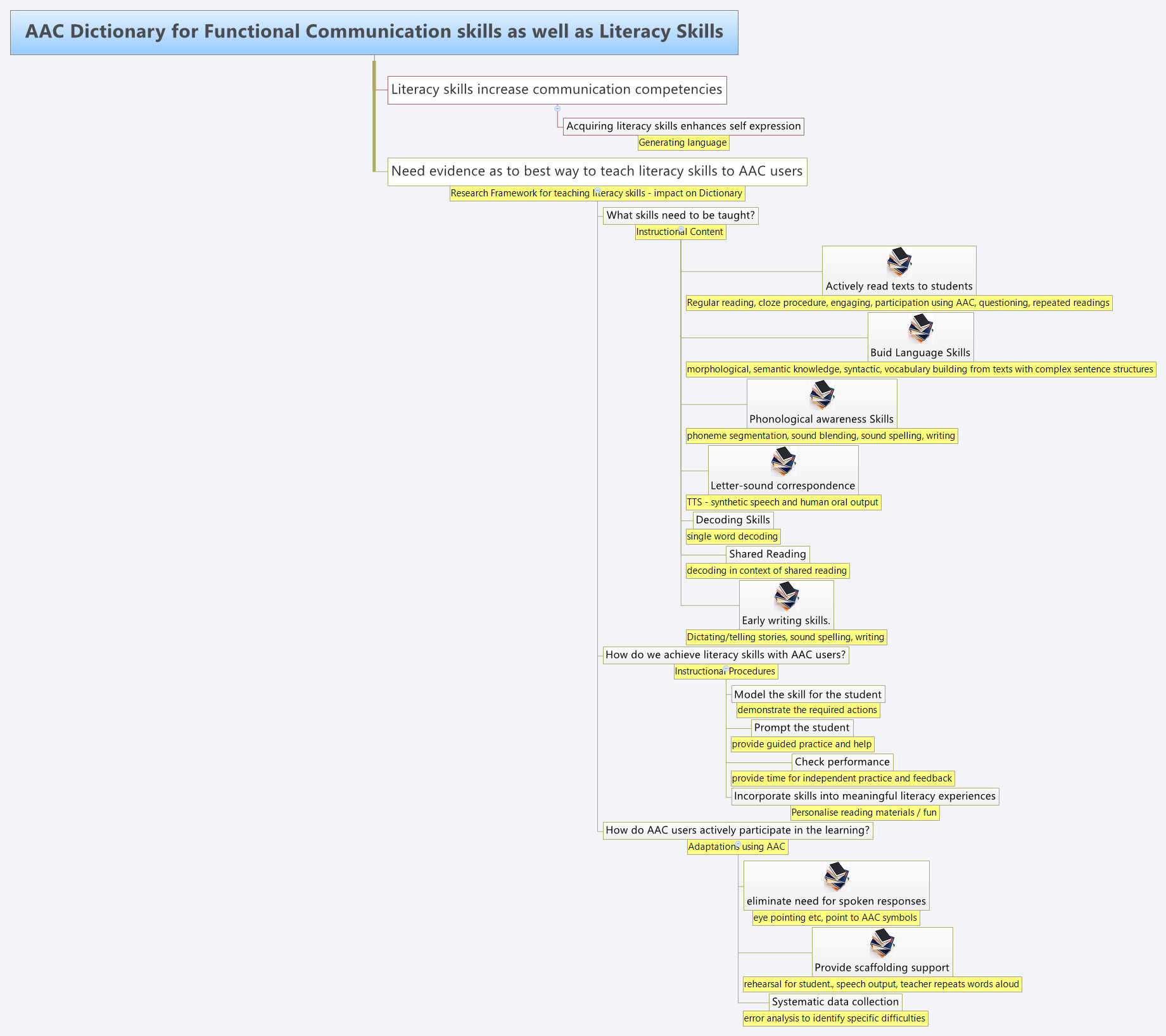

I have taken the main elements and added the image of a set of books to each section that would have an impact on the symbol dictionary. The text version of the mindmap can also be downloaded.

There is the importance of being able to link the words learnt in the reading exercise to symbols available in the dictionary to enable AAC users to show they have understood or remembered the word. This means that there will need to be a way of adding symbols and words at anytime with guidance for image creation and categorisation.

As mentioned offering phoneme segmentation and ways of showing an understanding of sound blending is important. Speech output whether this is human or a good quality synthetic computer generated voice should be available to encourage, reinforce and enhance literacy skills.

The information for this blog came from a “literacy program developed and evaluated by Dr. Janice Light and Dr. David McNaughton through a research grant (#H133E030018) funded by the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) as part of the AAC-RERC.” I will be adding the academic papers related to this subject to our Useful Articles page but here are some that were included at the end of the AAC-RERC slides.

References

Light, J. Kelford Smith, A. (1993). The home literacy experiences of preschoolers who use augmentative communication systems and of their nondisabled peers.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 910-25.

Light, J. McNaughton, D. (1993). Literacy and augmentative and alternative communication (AAC): The expectations and priorities of parents and teachers. Topics in Language Disorders, 13(2), 33-46.

Millar, D., Light, J., McNaughton, D. (2004). The effect of direct instruction and Writer’s Workshop on the early writing skills of children who use Augmentative and

Alternative Communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 20, 164-178.

Fallon, K., Light, J., McNaughton, D., Drager, K. Hammer, C. (2004). The effects of direct instruction on the single-word reading skills of children who require Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). Journal of Speech Language Hearing Research, 47,

1424-1439.

Kelford-Smith, A., Thurston, S., Light, J., Parnes, P. O’Keefe, B. (1989). The form and use of written communication produced by nonspeaking physically disabled individuals using microcomputers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 5, 115- 124.

Light, J., Binger, C., Kelford Smith, A. (1994). The story reading interactions of preschoolers who use augmentative and alternative communication and their mothers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10,255-268. 15

There is also a Bibliography: Literacy and AAC, Literacy and Disability provided by Communication Disabilities Access Canada (CDAC)