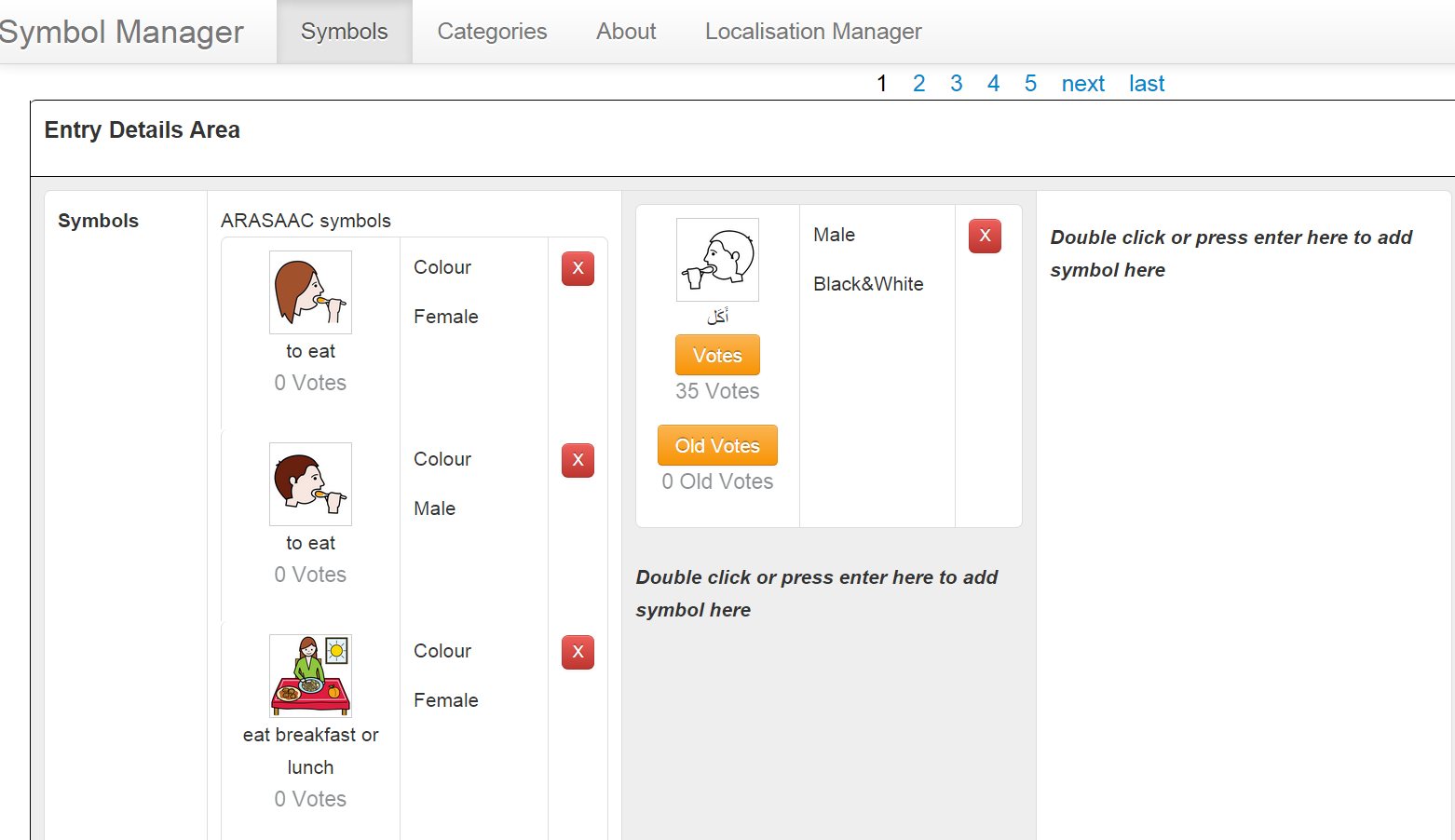

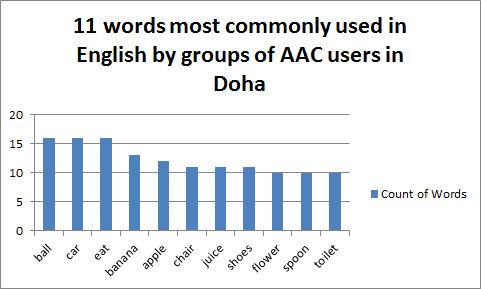

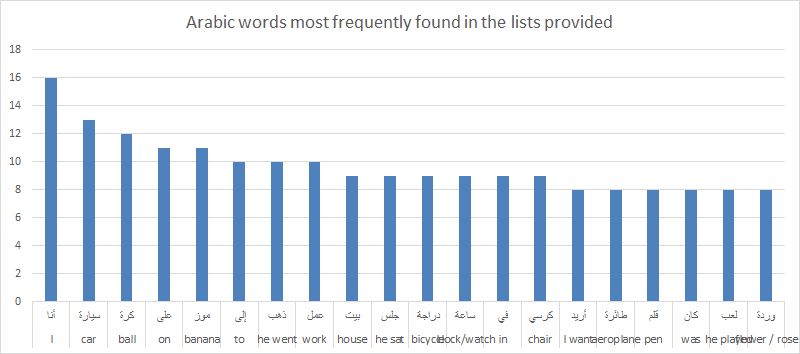

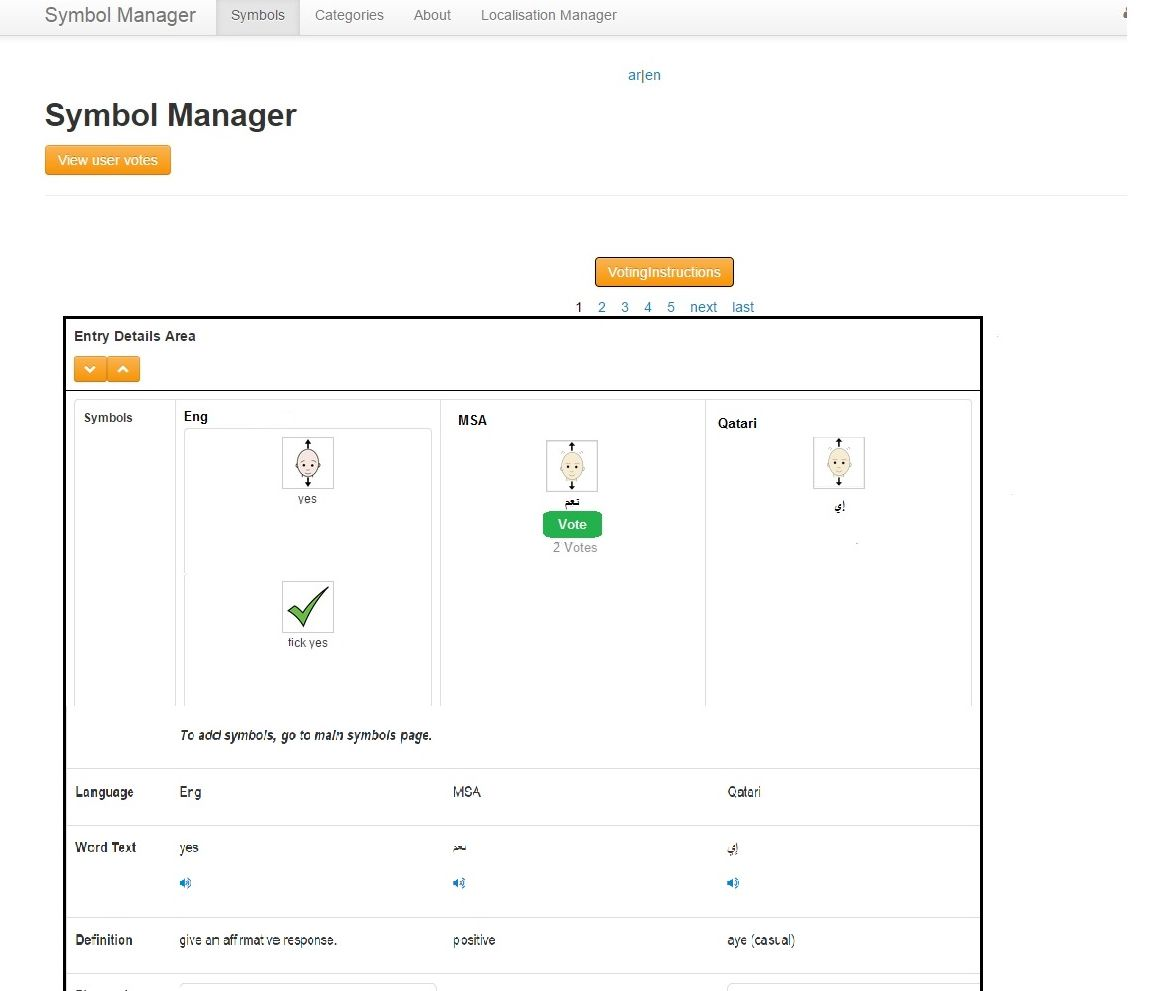

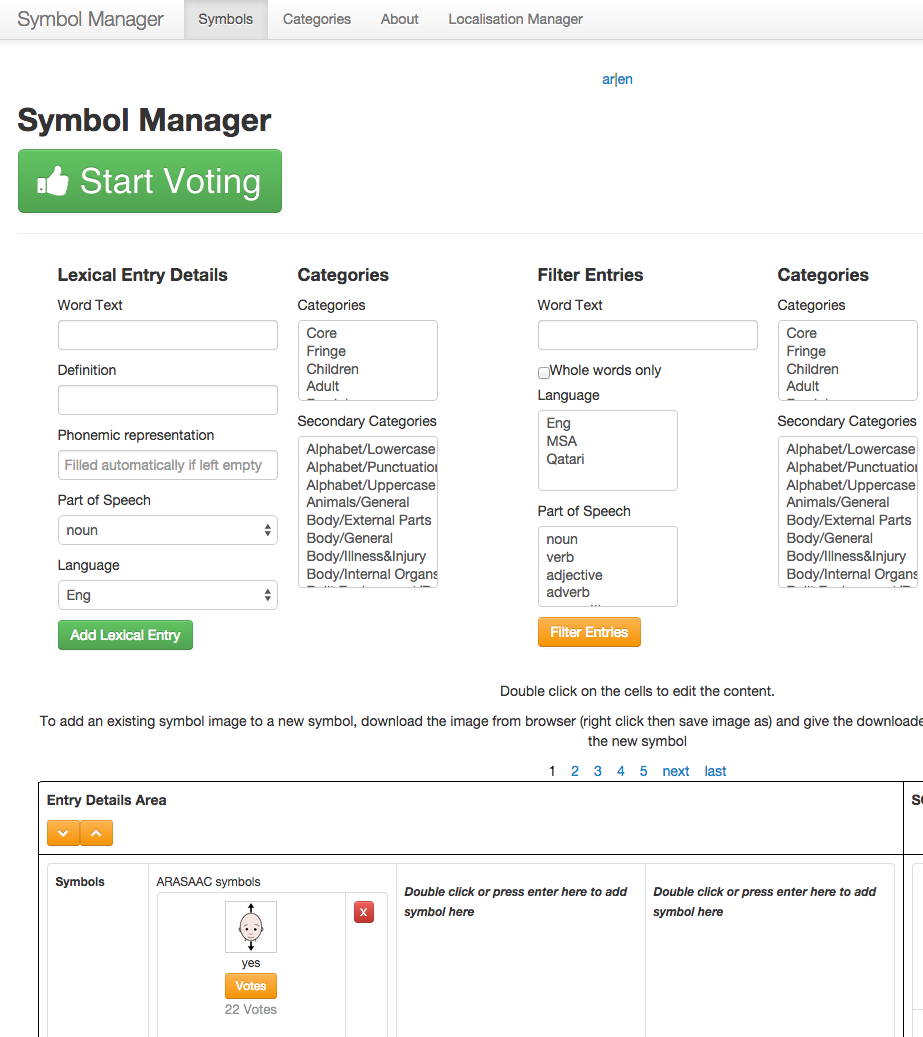

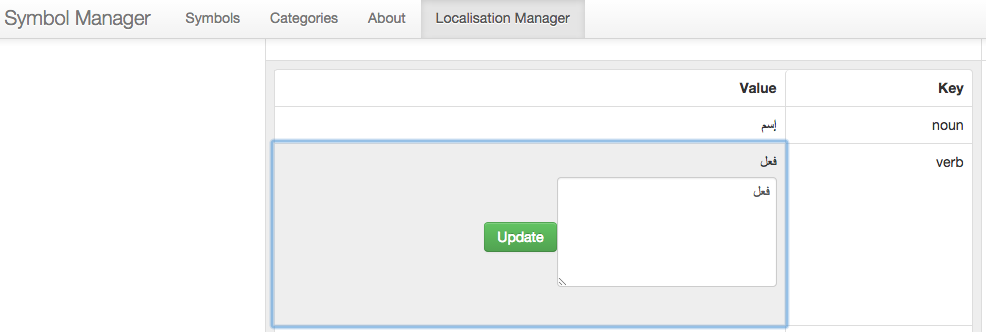

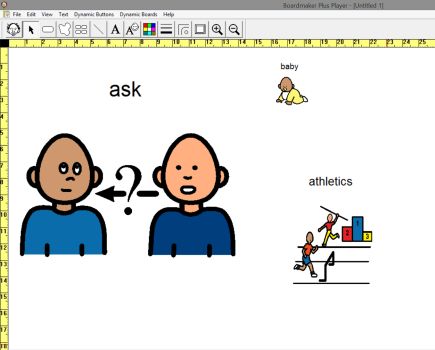

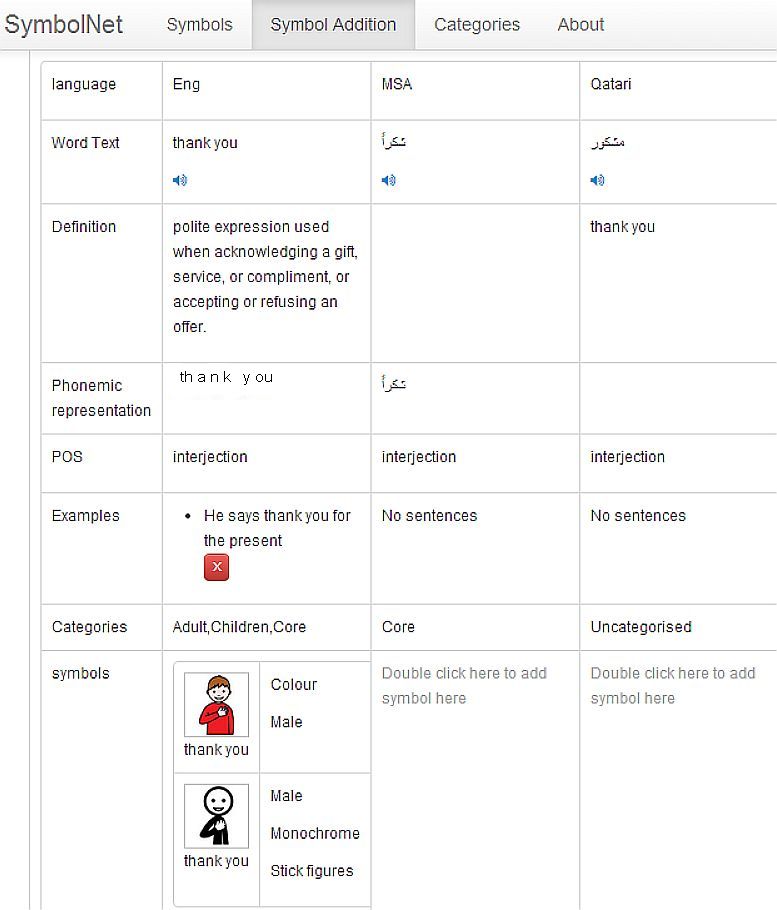

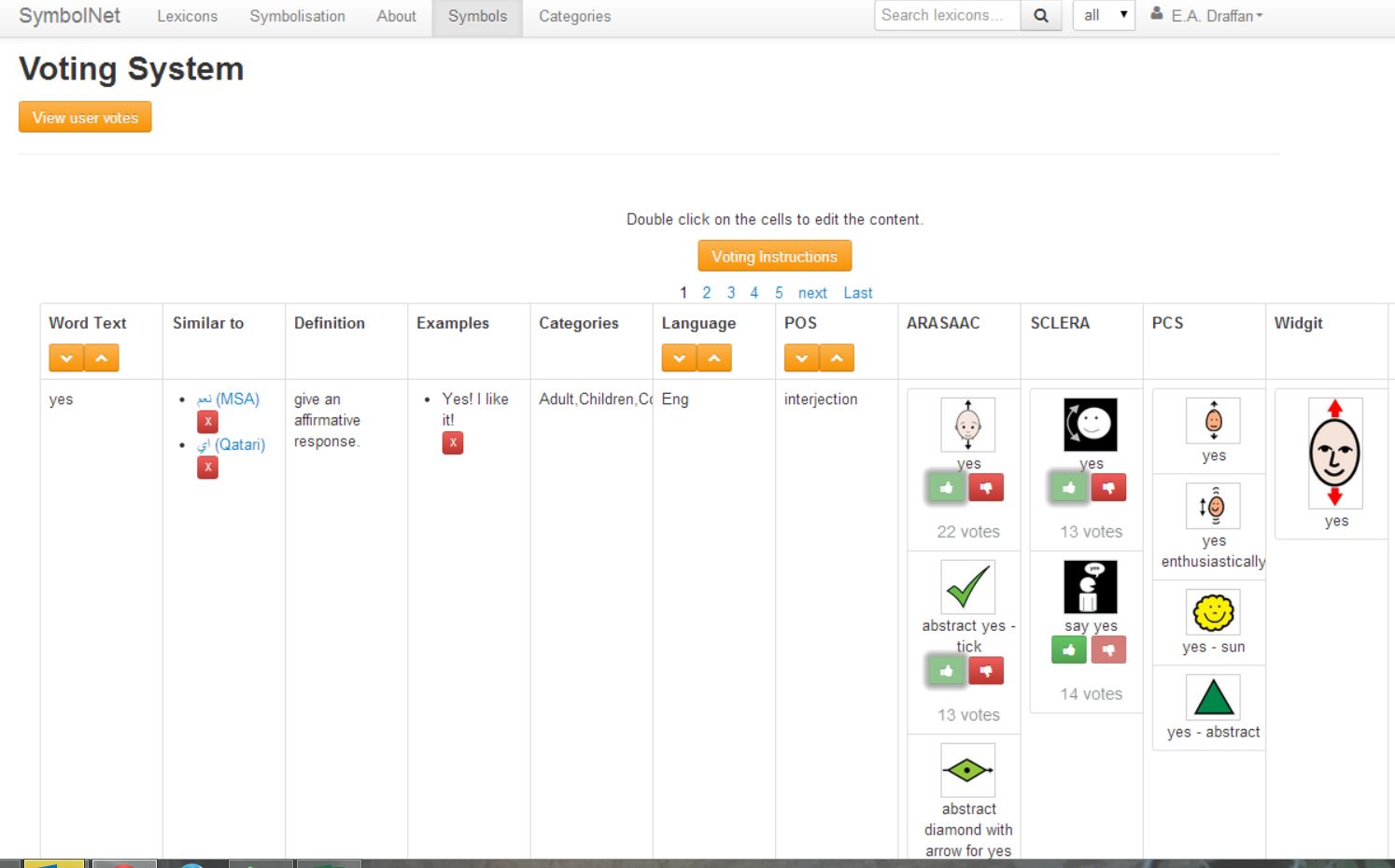

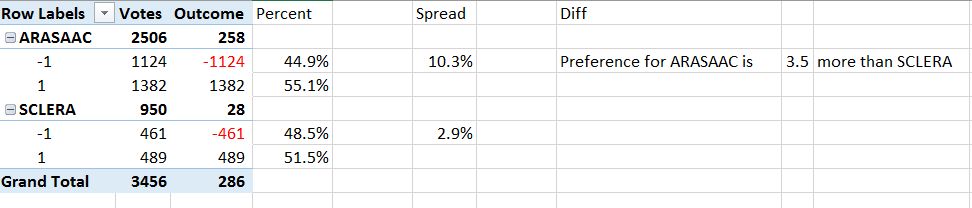

Whilst we analyse the voting for the symbols and check the results against the core English vocabulary lists provided by Tullah from the various Doha groups of AAC users we have been investigating how we could tag and store the symbols and their matching lexicons in English and Arabic.

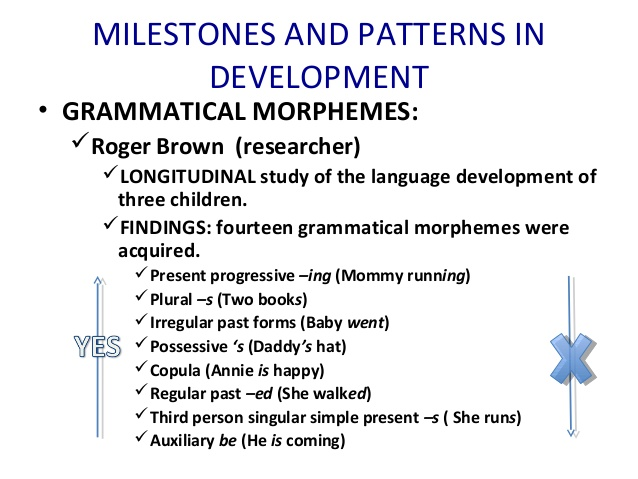

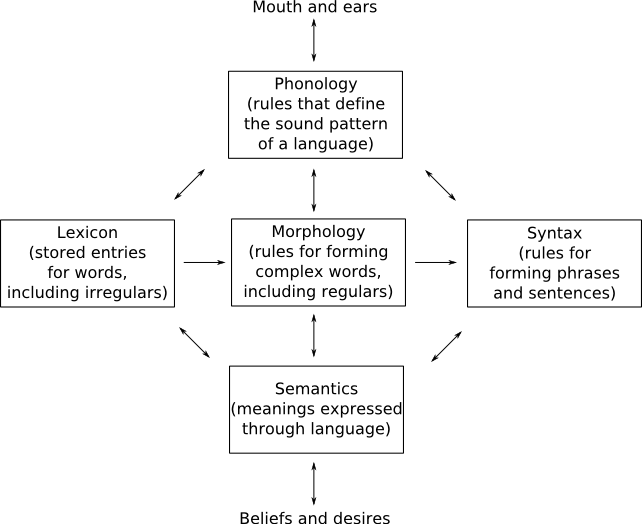

Meetings with Professor Annalu Waller in Dundee and Simon Judge in Sheffield confirmed suspicions that if we wanted to ensure that the dictionary not only coped with the communication side of symbol use and also encouraged literacy skills there needed to be links to the way words were made up of phonemes. Research has shown that phonemic awareness can be used as a predictor for reading ability (Gillon, 2004)

Teaching phonics has become a hot topic in UK Primary schools to the extent that even the newspapers have come up with lists of resources to aid teachers and parents. An example is the Guardian article in 2013 “How to teach … phonics”

But the dilemma is how we make a dictionary of words / multiwords linking to symbols that can also be searched by phonemes in English and Arabic for those who can often only listen to the sounds or may find it hard to say them or recognise their significance. Clearly this aspect of the dictionary is only for certain groups of symbol users who may have the ability to learn to read and write.

‘Synthetic phonics‘ is often used with ‘made-up’ words to encourage grapheme / phoneme recognition. However, as can be seen from the example, even those words introduced at primary school level may have letter combinations that can be pronounced in different ways, for instance in ‘geck’ the letter ‘g’ can be said with a hard sound or a soft sound in front of an ‘e’ (/dz/ or /g/). Children tend to be taught around

According to teaching documents provided by the Education Department at Oxford Brookes University: “In English, much more than in other languages,

- many letters or letter-combinations can commonly represent more than one sound – for example ea as in heat and head;

- most sounds can be spelt in more than one way – for example the vowel sound in heat is also commonly spelt as in he, see, chief and complete;

- Some very common words contain grapheme-phoneme correspondences that occur in few if any other words – for example one, two, are, said, great, people, laugh.” (TDA, 2011)

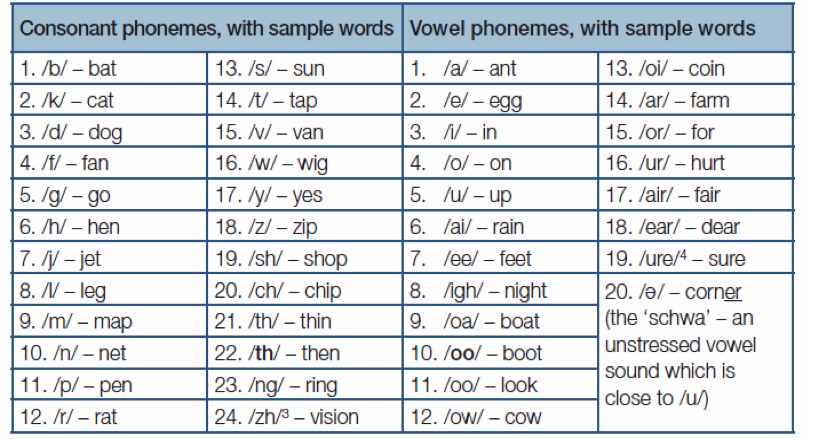

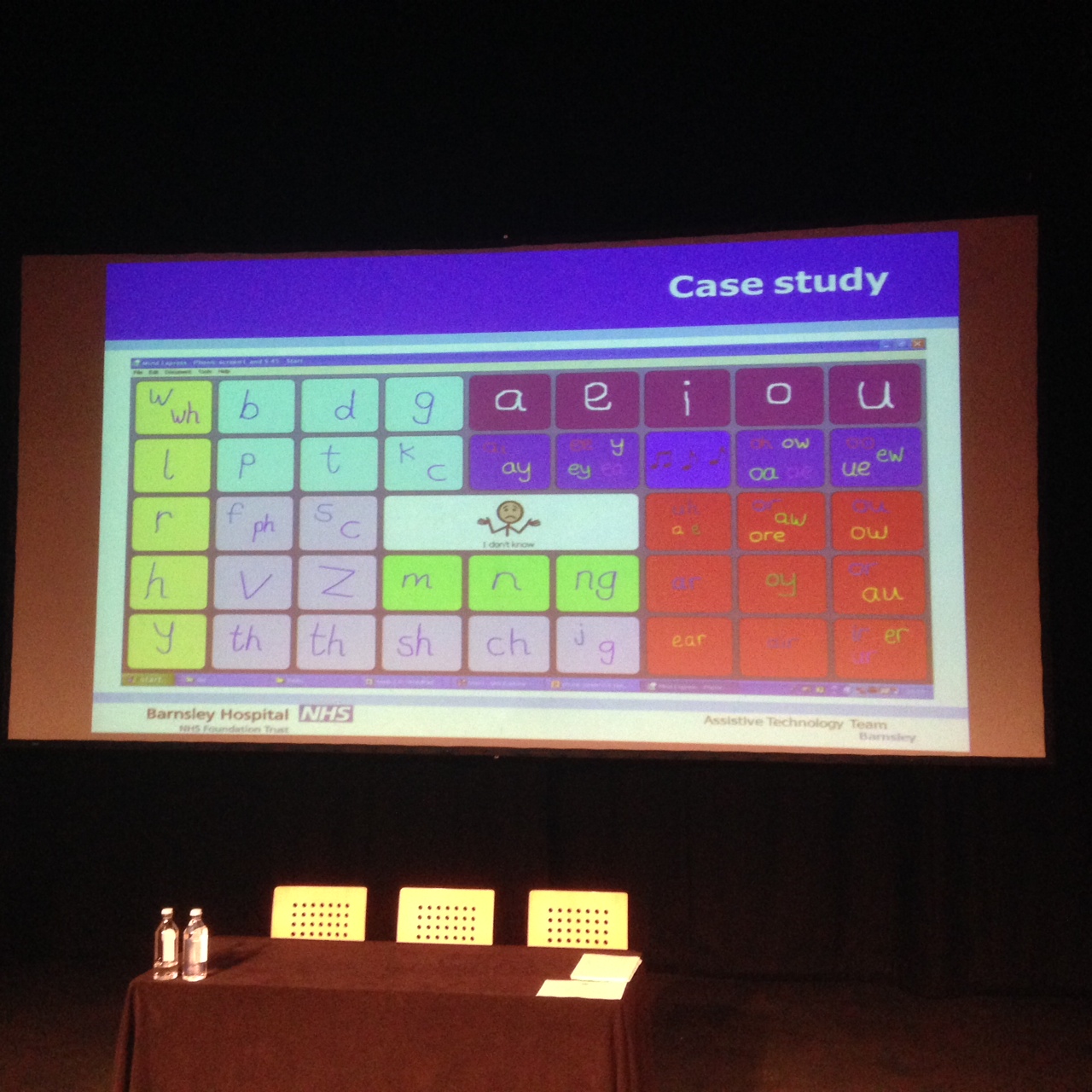

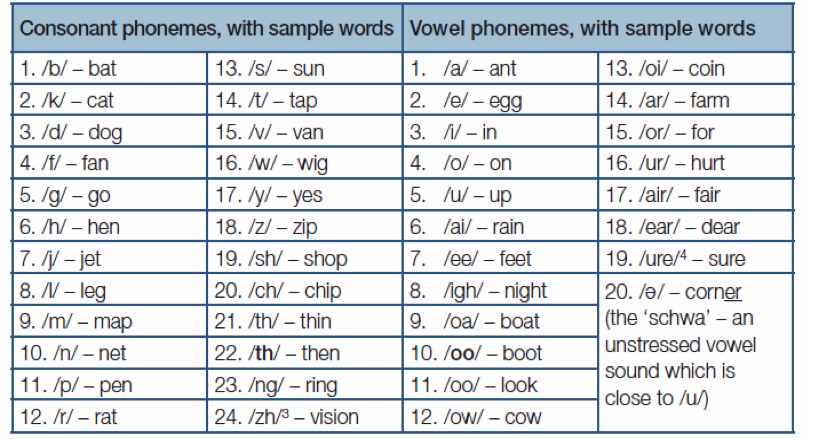

Children tend to learn the basic 44 phonemes in English which are represented below.

The Phoneme Table below lists the 44 phonemes of the English Language, from the National Strategies Standards’ phonics sounds. (DFES 2007)

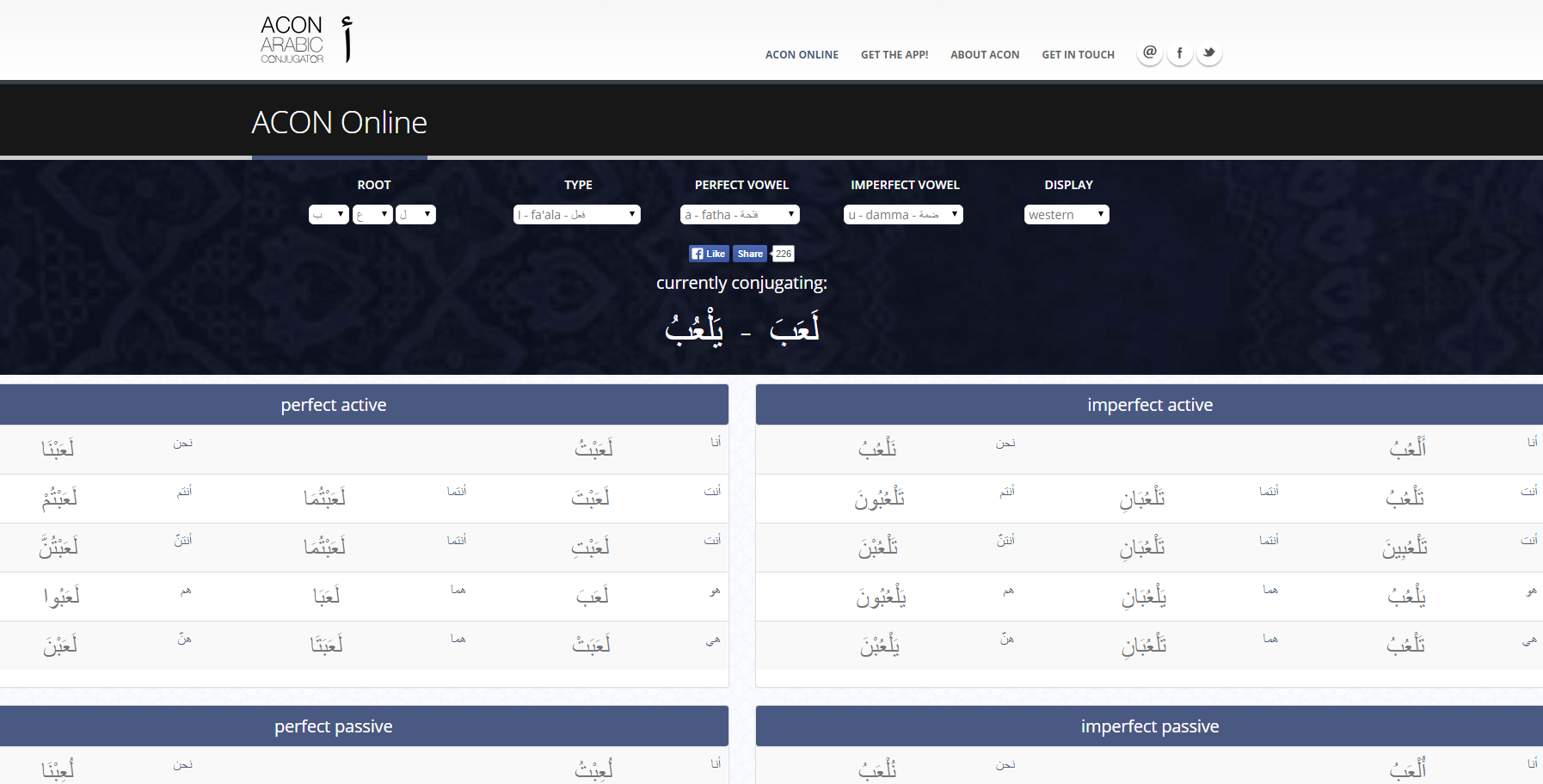

The good news is that in Arabic every letter combination has a set rule and although there may be many sounds that cannot be replicated in English the grapheme/phoneme representation is stable. The image below shows where there are overlaps between Arabic and English phonemes.

Research carried out by Amor and Maad (2013) working with Arabic speaking Tunisian children has shown that: (direct quote from their article)

The best performances of Good Readers confirm the idea supported by many researchers (e.g. Byrne et al., 1992; Gombert, 1992) that reading failure may manifest itself through a lack of phonemic awareness. The lowest results of the Preliterate children suggest that phonemic awareness does not develop spontaneously, but only in the specific context of learning to read an alphabetic script at school. This phenomenon was observed in many alphabetically written languages, such as English, French (Gillon, 2004; Morais et al., 1987), and Hebrew (Bentin et al., 1991; Oren, 2001).

The researchers found there were specific difficulties with phonemic segmentation for Arabic words across the cohort of “110 Tunisian children enrolled in primary education schools and kindergartens”. All their participants scored less well than expected in comparison to research results carried out in other languages. This was felt to be due to the diglossia nature of Arabic with colloquial Arabic often being spoken at home whereas Modern Standard Arabic is used in schools. Nevertheless, the children coped better with consonants in deletion tasks, for example /k/t/b/ that make up many words around reading and writing e,g /kataba/ (he wrote), /kutiba/ (it was written), /kutubun/ (books), etc.

Those learning to read in English tend to find it easier to mark initial and final phonemes as individual sounds with the medial one proving harder to work out. Amor and Maad (2013) found that their participants had difficulties across all three positions. “Divergence between the performances of Arabic-speaking and English-speaking children confirms that the representations about the consonantal segments were not the same. “

Summary

It appears that the ability to gain phoneme / grapheme awareness is harder in Arabic than some other languages and that the total number of consonant segments in Arabic are higher than most languages but the number of vowel based segments are lower (Newman, 2002)

One idea when creating the lexical entry in the symbol dictionary is to include the representative phonemes with their diacritics, their change in shape (depending on the position in the word) and the sound they make using text to speech or recorded speech.

References

Abu-Rabia, S. (2001). The role of vowels in reading Semitic scripts: Data from Arabic and Hebrew. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 14, 39-59.

Amaryeh, M. M., Dyson, A.T. (1998). The Acquisition of Arabic Consonants. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 41, 642

Amor P. D. M., & Maad, R. Ben. (2013). The Role of Arabic Orthographic Literacy in the Phonological Awareness of Tunisian Children (April). Retrieved from http://www.ijonte.org/FileUpload/ks63207/File/02.amor.pdf

Bentin, S., Hammer, R. & Cahan, C. (1991). The effects of ageing and first grade schooling on the development of phonological awareness. Psychological science, 2(4) 271-274.

Byrne, B., Freebody, P. & Gates, A. (1992). Longitudinal data on the relation of word-reading strategies to comprehension, reading time and phonemic awareness. Reading, Research Quarterly, 27, 141-151.

Department of Education and Skills (2007) Letters and Sounds: Principles and Practice of High Quality Phonics – Primary National Strategy ( PDF Downloaded July 30th, 2014)

Gombert, J.E. (1992). Metalinguistic development. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gillon, G. (2004). Phonological awareness: From research to practice. New York: Guilford Press.

Kurtz, R. (2010). Phonemic awareness affects speech and literacy. Speech-Language-Development. Retrieved from http://www.speech-language-development.com/phonemic-awareness.html

Khomsi, A. (1993). L’epreuve collective d’identification de mots. Nantes : University of Nantes.

Liberman, I., Shankweiler, D., Fisher, F. & Carter, B. (1974). Explicit syllable and phoneme segmentation in the young child, Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 18, 201-212.

MacDonald, G. & Cornwall, A. (1995). The relationship between phonological awareness and reading and spelling achievement eleven years later. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 28(8) 523-527.

Morais, J., Alegria, J., & Content, A. (1987). The relationship between segmental analysis and alphabetic literacy: An interactive view. Cahiers de Psychologie Cognitive, 7, 415-438.

Newman, Daniel L. 2002. The phonetic status of Arabic within the world’s languages.

Antwerp Papers in Linguistics, 100:63–75 http://uahost.uantwerpen.be/apil/apil100/Arabic1.pdf

Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2005). Correlates of reading fluency in Arabic: Diglossic and orthographic factors. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18, 559-582. International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications April 2013 Volume: 4 Issue: 2 Article: 02 ISSN 1309-6249

The Training and Development Agency for Schools (TDA) (2011) Systematic synthetic phonics in initial teaching training: Guidance and support materials. (Word document downloaded July 30th, 2014)

Vandervelden, M., & Siegel, L. (1995). Phonological recoding and phonemic awareness in early literacy: Developmental approach. Reading Research Quarterly, 30 (4). 854-875.

Ziegler, J. & Goswami, U. (2005). Reading acquisition, developmental dyslexia and skilled reading across languages. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 3–29.

How do we represent the past and the future when the writing is going from right to left – is the arrow for past going from right to left or left to right? Widgit offer a very good example of how this is achieved in English with their symbols.

How do we represent the past and the future when the writing is going from right to left – is the arrow for past going from right to left or left to right? Widgit offer a very good example of how this is achieved in English with their symbols.

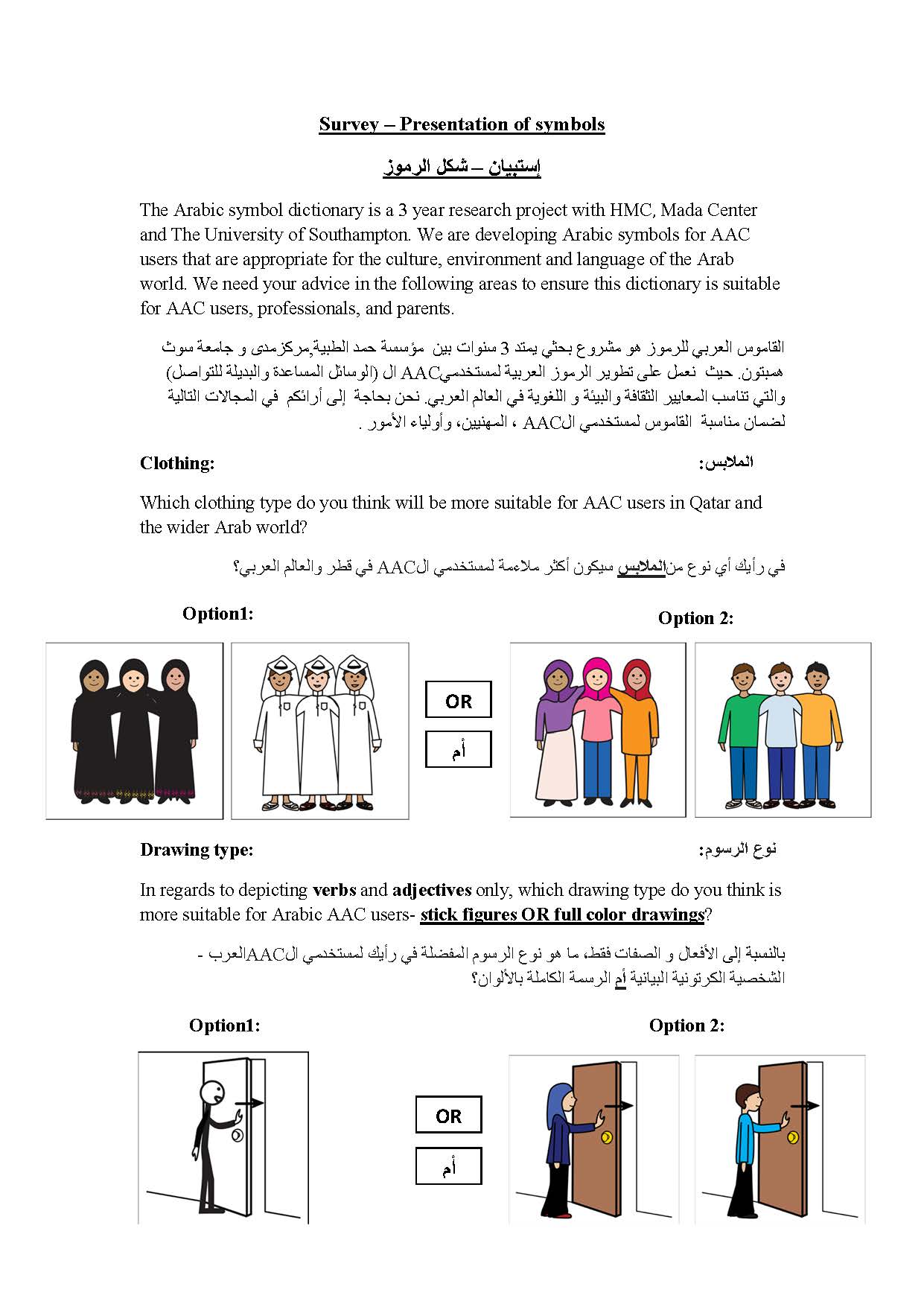

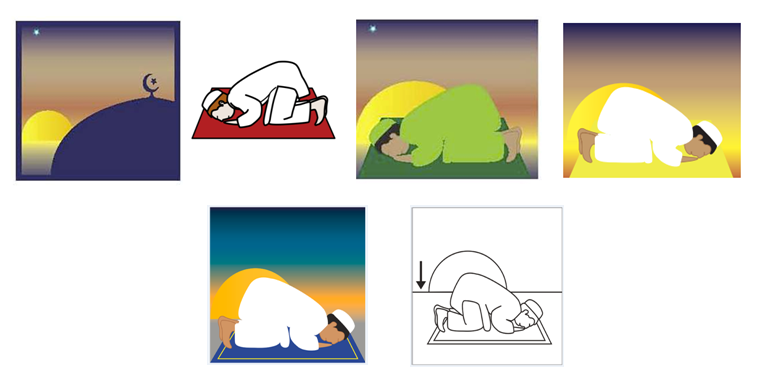

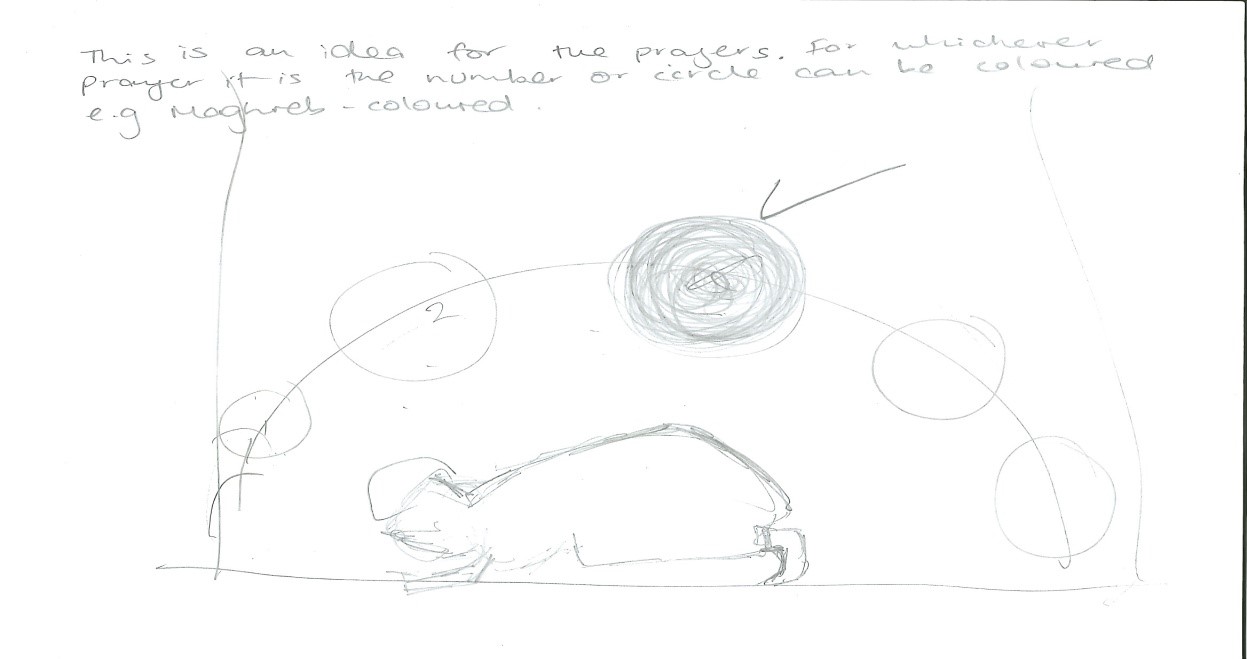

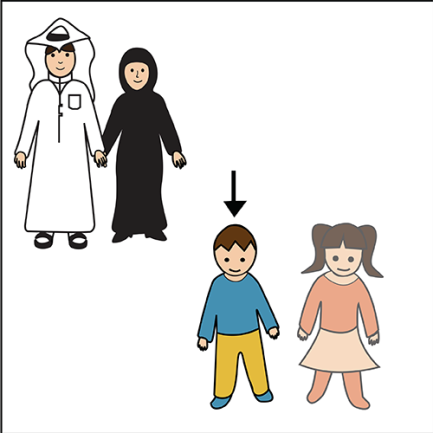

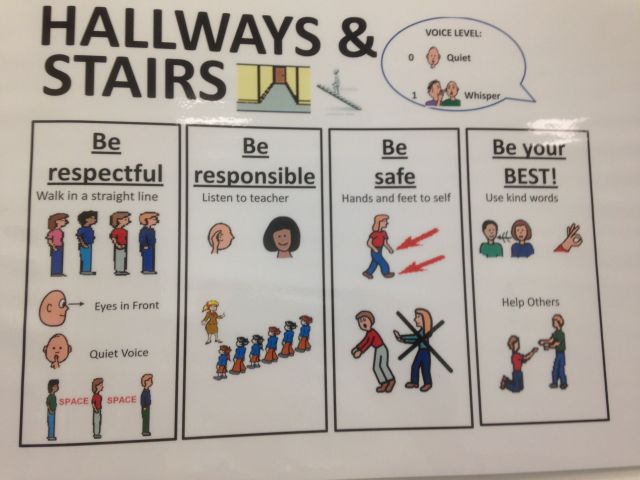

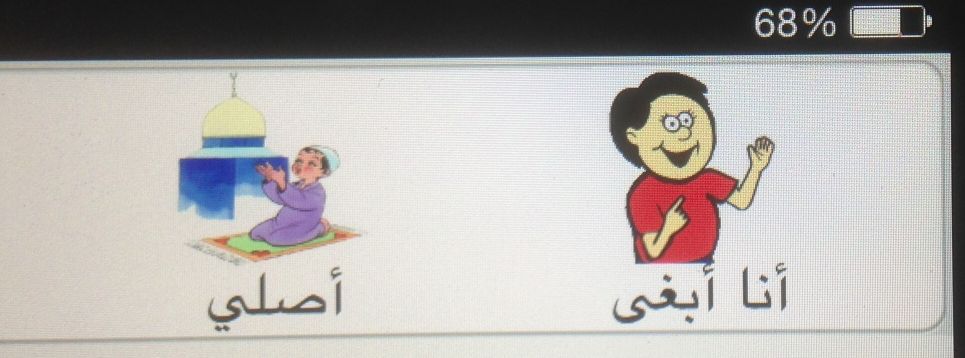

Because there have been some concerns about the way action symbols for verbs are portrayed and the type of clothing needed across all the symbols it was decided that we needed to increase the number of people involved in making these decisions so a survey is being sent out across several organisations with AAC users in the hope that we receive clear direction.

Because there have been some concerns about the way action symbols for verbs are portrayed and the type of clothing needed across all the symbols it was decided that we needed to increase the number of people involved in making these decisions so a survey is being sent out across several organisations with AAC users in the hope that we receive clear direction.

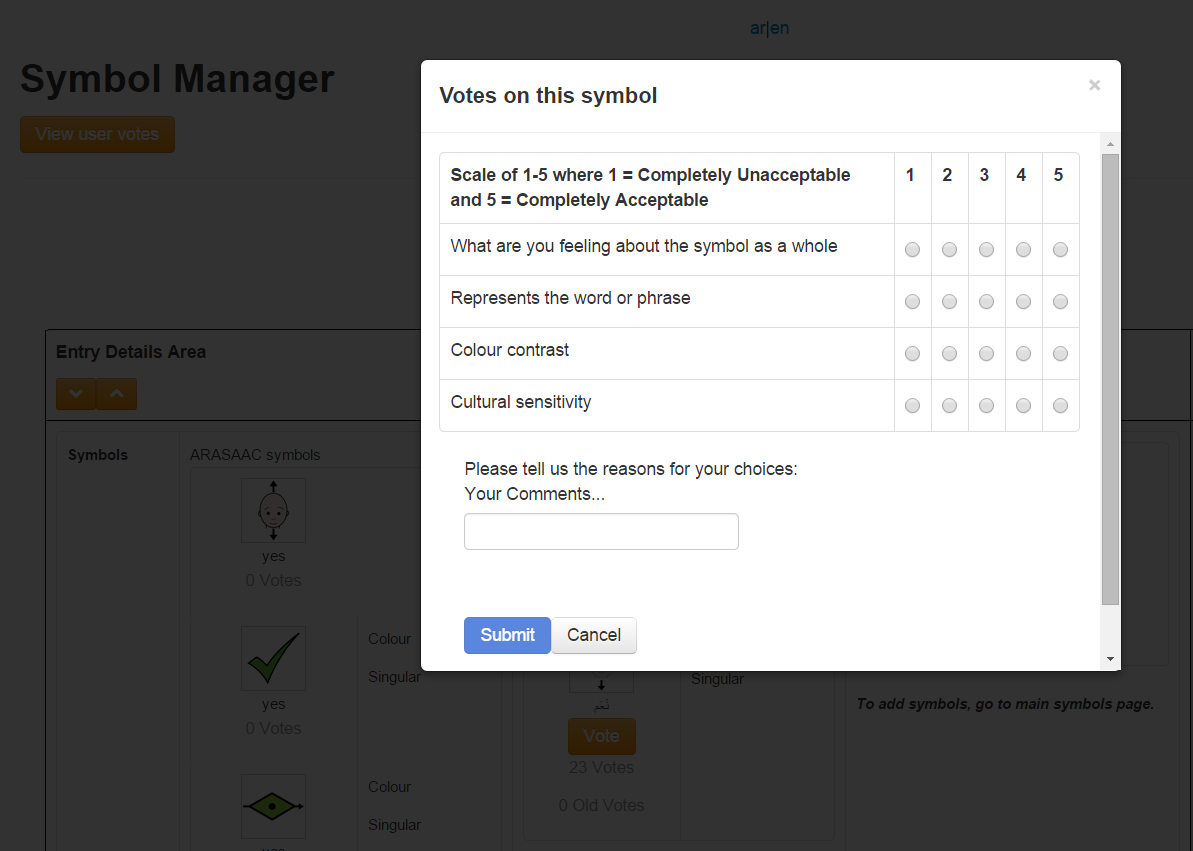

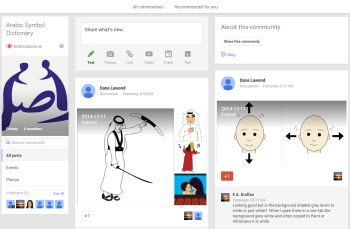

One of the ways we have been working on symbols that has greatly speeded up interaction between team members has been the use of Google+ with images being uploaded and our votes and comments being monitored by Dana before she finally uploads the images to the Symbol Manager for voting by the AAC Forum.

One of the ways we have been working on symbols that has greatly speeded up interaction between team members has been the use of Google+ with images being uploaded and our votes and comments being monitored by Dana before she finally uploads the images to the Symbol Manager for voting by the AAC Forum.

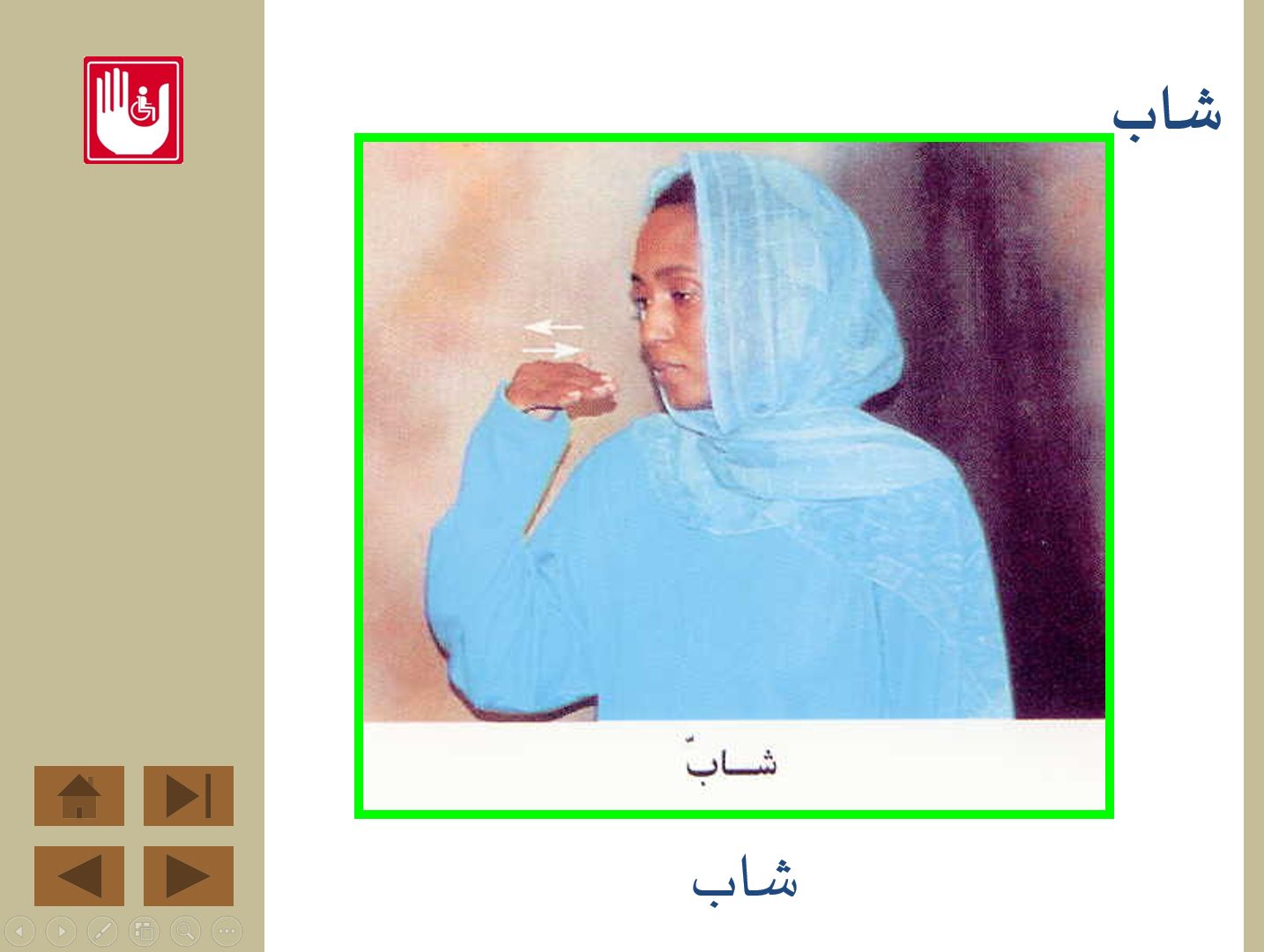

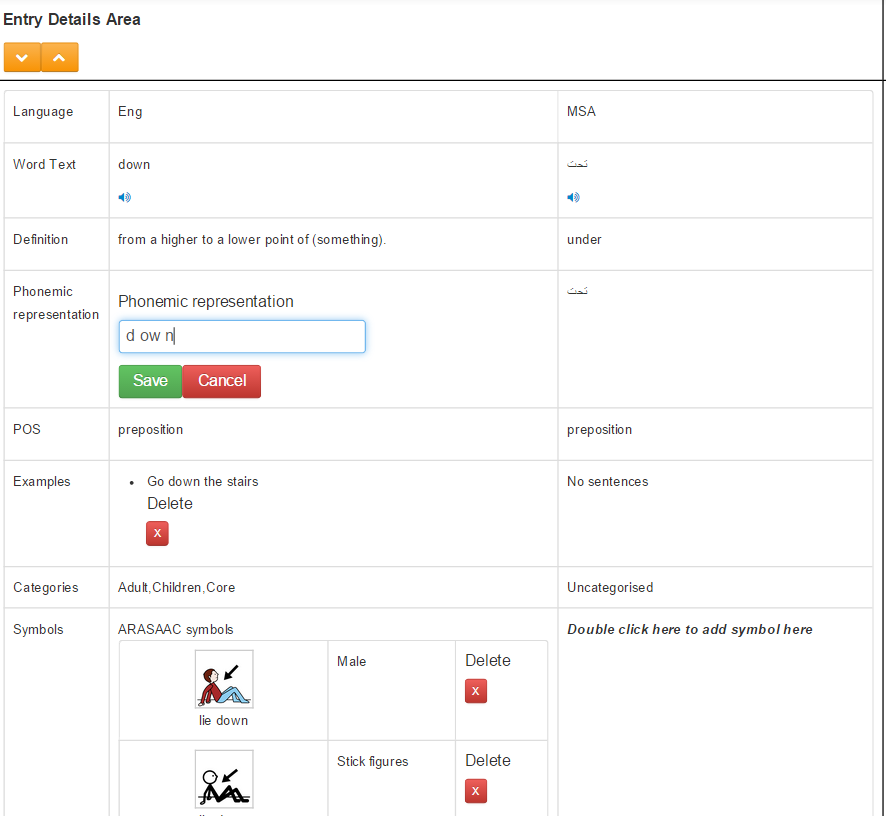

Symbols can be deleted one by one using the orange framed back arrow

Symbols can be deleted one by one using the orange framed back arrow The entire phrase/sentence can be deleted using the red framed trash can

The entire phrase/sentence can be deleted using the red framed trash can The symbols are changed into a choice of sentences by selecting the green framed rotor

The symbols are changed into a choice of sentences by selecting the green framed rotor Should one of the categories on the right be chosen, the user returns to the home page using blue framed arrow

Should one of the categories on the right be chosen, the user returns to the home page using blue framed arrow The book with open pages toggles access to second language – Arabic or English.

The book with open pages toggles access to second language – Arabic or English. The Text to Speech in Arabic is activated by highlighting the text and using ATbar speech output if you do not have Arabic on your computer

The Text to Speech in Arabic is activated by highlighting the text and using ATbar speech output if you do not have Arabic on your computer